Quantitative Economics with Python

Cass-Koopmans Planning Problem

20. Cass-Koopmans Planning Problem¶

Contents

20.1. Overview¶

This lecture and lecture Cass-Koopmans Competitive Equilibrium describe a model that Tjalling Koopmans [Koo65] and David Cass [Cas65] used to analyze optimal growth.

The model can be viewed as an extension of the model of Robert Solow described in an earlier lecture but adapted to make the saving rate the outcome of an optimal choice.

(Solow assumed a constant saving rate determined outside the model.)

We describe two versions of the model, one in this lecture and the other in Cass-Koopmans Competitive Equilibrium.

Together, the two lectures illustrate what is, in fact, a more general connection between a planned economy and a decentralized economy organized as a competitive equilibrium.

This lecture is devoted to the planned economy version.

The lecture uses important ideas including

A min-max problem for solving a planning problem.

A shooting algorithm for solving difference equations subject to initial and terminal conditions.

A turnpike property that describes optimal paths for long but finite-horizon economies.

Let’s start with some standard imports:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (11, 5) #set default figure size

from numba import njit, float64

from numba.experimental import jitclass

import numpy as np

20.2. The Model¶

Time is discrete and takes values \(t = 0, 1 , \ldots, T\) where \(T\) is finite.

(We’ll study a limiting case in which \(T = + \infty\) before concluding).

A single good can either be consumed or invested in physical capital.

The consumption good is not durable and depreciates completely if not consumed immediately.

The capital good is durable but depreciates some each period.

We let \(C_t\) be a nondurable consumption good at time \(t\).

Let \(K_t\) be the stock of physical capital at time \(t\).

Let \(\vec{C}\) = \(\{C_0,\dots, C_T\}\) and \(\vec{K}\) = \(\{K_0,\dots,K_{T+1}\}\).

A representative household is endowed with one unit of labor at each \(t\) and likes the consumption good at each \(t\).

The representative household inelastically supplies a single unit of labor \(N_t\) at each \(t\), so that \(N_t =1 \text{ for all } t \in [0,T]\).

The representative household has preferences over consumption bundles ordered by the utility functional:

where \(\beta \in (0,1)\) is a discount factor and \(\gamma >0\) governs the curvature of the one-period utility function with larger \(\gamma\) implying more curvature.

Note that

satisfies \(u'>0,u''<0\).

\(u' > 0\) asserts that the consumer prefers more to less.

\(u''< 0\) asserts that marginal utility declines with increases in \(C_t\).

We assume that \(K_0 > 0\) is an exogenous initial capital stock.

There is an economy-wide production function

with \(0 < \alpha<1\), \(A > 0\).

A feasible allocation \(\vec{C}, \vec{K}\) satisfies

where \(\delta \in (0,1)\) is a depreciation rate of capital.

20.3. Planning Problem¶

A planner chooses an allocation \(\{\vec{C},\vec{K}\}\) to maximize (20.1) subject to (20.4).

Let \(\vec{\mu}=\{\mu_0,\dots,\mu_T\}\) be a sequence of nonnegative Lagrange multipliers.

To find an optimal allocation, form a Lagrangian

and then pose the following min-max problem:

Extremization means maximization with respect to \(\vec{C}, \vec{K}\) and minimization with respect to \(\vec{\mu}\).

Our problem satisfies conditions that assure that required second-order conditions are satisfied at an allocation that satisfies the first-order conditions that we are about to compute.

Before computing first-order conditions, we present some handy formulas.

20.3.1. Useful Properties of Linearly Homogeneous Production Function¶

The following technicalities will help us.

Notice that

Define the output per-capita production function

whose argument is capital per-capita.

It is useful to recall the following calculations for the marginal product of capital

and the marginal product of labor

20.3.2. First-order necessary conditions¶

We now compute first order necessary conditions for extremization of the Lagrangian:

In computing (20.9) we recognize that \(K_t\) appears in both the time \(t\) and time \(t-1\) feasibility constraints.

(20.10) comes from differentiating with respect to \(K_{T+1}\) and applying the following Karush-Kuhn-Tucker condition (KKT) (see Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions):

Combining (20.7) and (20.8) gives

which can be rearranged to become

Applying the inverse of the utility function on both sides of the above equation gives

which for our utility function (20.2) becomes the consumption Euler equation

Below we define a jitclass that stores parameters and functions

that define our economy.

planning_data = [

('γ', float64), # Coefficient of relative risk aversion

('β', float64), # Discount factor

('δ', float64), # Depreciation rate on capital

('α', float64), # Return to capital per capita

('A', float64) # Technology

]

@jitclass(planning_data)

class PlanningProblem():

def __init__(self, γ=2, β=0.95, δ=0.02, α=0.33, A=1):

self.γ, self.β = γ, β

self.δ, self.α, self.A = δ, α, A

def u(self, c):

'''

Utility function

ASIDE: If you have a utility function that is hard to solve by hand

you can use automatic or symbolic differentiation

See https://github.com/HIPS/autograd

'''

γ = self.γ

return c ** (1 - γ) / (1 - γ) if γ!= 1 else np.log(c)

def u_prime(self, c):

'Derivative of utility'

γ = self.γ

return c ** (-γ)

def u_prime_inv(self, c):

'Inverse of derivative of utility'

γ = self.γ

return c ** (-1 / γ)

def f(self, k):

'Production function'

α, A = self.α, self.A

return A * k ** α

def f_prime(self, k):

'Derivative of production function'

α, A = self.α, self.A

return α * A * k ** (α - 1)

def f_prime_inv(self, k):

'Inverse of derivative of production function'

α, A = self.α, self.A

return (k / (A * α)) ** (1 / (α - 1))

def next_k_c(self, k, c):

''''

Given the current capital Kt and an arbitrary feasible

consumption choice Ct, computes Kt+1 by state transition law

and optimal Ct+1 by Euler equation.

'''

β, δ = self.β, self.δ

u_prime, u_prime_inv = self.u_prime, self.u_prime_inv

f, f_prime = self.f, self.f_prime

k_next = f(k) + (1 - δ) * k - c

c_next = u_prime_inv(u_prime(c) / (β * (f_prime(k_next) + (1 - δ))))

return k_next, c_next

We can construct an economy with the Python code:

pp = PlanningProblem()

20.4. Shooting Algorithm¶

We use shooting to compute an optimal allocation \(\vec{C}, \vec{K}\) and an associated Lagrange multiplier sequence \(\vec{\mu}\).

The first-order necessary conditions (20.7), (20.8), and (20.9) for the planning problem form a system of difference equations with two boundary conditions:

\(K_0\) is a given initial condition for capital

\(K_{T+1} =0\) is a terminal condition for capital that we deduced from the first-order necessary condition for \(K_{T+1}\) the KKT condition (20.11)

We have no initial condition for the Lagrange multiplier \(\mu_0\).

If we did, our job would be easy:

Given \(\mu_0\) and \(k_0\), we could compute \(c_0\) from equation (20.7) and then \(k_1\) from equation (20.9) and \(\mu_1\) from equation (20.8).

We could continue in this way to compute the remaining elements of \(\vec{C}, \vec{K}, \vec{\mu}\).

But we don’t have an initial condition for \(\mu_0\), so this won’t work.

Indeed, part of our task is to compute the optimal value of \(\mu_0\).

To compute \(\mu_0\) and the other objects we want, a simple modification of the above procedure will work.

It is called the shooting algorithm.

It is an instance of a guess and verify algorithm that consists of the following steps:

Guess an initial Lagrange multiplier \(\mu_0\).

Apply the simple algorithm described above.

Compute \(k_{T+1}\) and check whether it equals zero.

If \(K_{T+1} =0\), we have solved the problem.

If \(K_{T+1} > 0\), lower \(\mu_0\) and try again.

If \(K_{T+1} < 0\), raise \(\mu_0\) and try again.

The following Python code implements the shooting algorithm for the planning problem.

We actually modify the algorithm slightly by starting with a guess for \(c_0\) instead of \(\mu_0\) in the following code.

@njit

def shooting(pp, c0, k0, T=10):

'''

Given the initial condition of capital k0 and an initial guess

of consumption c0, computes the whole paths of c and k

using the state transition law and Euler equation for T periods.

'''

if c0 > pp.f(k0):

print("initial consumption is not feasible")

return None

# initialize vectors of c and k

c_vec = np.empty(T+1)

k_vec = np.empty(T+2)

c_vec[0] = c0

k_vec[0] = k0

for t in range(T):

k_vec[t+1], c_vec[t+1] = pp.next_k_c(k_vec[t], c_vec[t])

k_vec[T+1] = pp.f(k_vec[T]) + (1 - pp.δ) * k_vec[T] - c_vec[T]

return c_vec, k_vec

We’ll start with an incorrect guess.

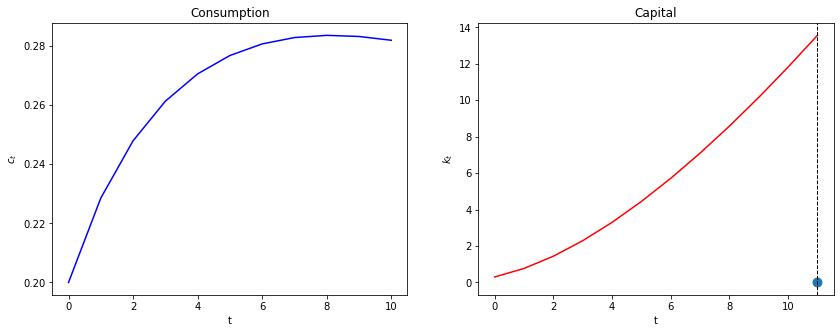

paths = shooting(pp, 0.2, 0.3, T=10)

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5))

colors = ['blue', 'red']

titles = ['Consumption', 'Capital']

ylabels = ['$c_t$', '$k_t$']

T = paths[0].size - 1

for i in range(2):

axs[i].plot(paths[i], c=colors[i])

axs[i].set(xlabel='t', ylabel=ylabels[i], title=titles[i])

axs[1].scatter(T+1, 0, s=80)

axs[1].axvline(T+1, color='k', ls='--', lw=1)

plt.show()

Evidently, our initial guess for \(\mu_0\) is too high, so initial consumption too low.

We know this because we miss our \(K_{T+1}=0\) target on the high side.

Now we automate things with a search-for-a-good \(\mu_0\) algorithm that stops when we hit the target \(K_{t+1} = 0\).

We use a bisection method.

We make an initial guess for \(C_0\) (we can eliminate \(\mu_0\) because \(C_0\) is an exact function of \(\mu_0\)).

We know that the lowest \(C_0\) can ever be is \(0\) and the largest it can be is initial output \(f(K_0)\).

Guess \(C_0\) and shoot forward to \(T+1\).

If \(K_{T+1}>0\), we take it to be our new lower bound on \(C_0\).

If \(K_{T+1}<0\), we take it to be our new upper bound.

Make a new guess for \(C_0\) that is halfway between our new upper and lower bounds.

Shoot forward again, iterating on these steps until we converge.

When \(K_{T+1}\) gets close enough to \(0\) (i.e., within an error tolerance bounds), we stop.

@njit

def bisection(pp, c0, k0, T=10, tol=1e-4, max_iter=500, k_ter=0, verbose=True):

# initial boundaries for guess c0

c0_upper = pp.f(k0)

c0_lower = 0

i = 0

while True:

c_vec, k_vec = shooting(pp, c0, k0, T)

error = k_vec[-1] - k_ter

# check if the terminal condition is satisfied

if np.abs(error) < tol:

if verbose:

print('Converged successfully on iteration ', i+1)

return c_vec, k_vec

i += 1

if i == max_iter:

if verbose:

print('Convergence failed.')

return c_vec, k_vec

# if iteration continues, updates boundaries and guess of c0

if error > 0:

c0_lower = c0

else:

c0_upper = c0

c0 = (c0_lower + c0_upper) / 2

def plot_paths(pp, c0, k0, T_arr, k_ter=0, k_ss=None, axs=None):

if axs is None:

fix, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(16, 4))

ylabels = ['$c_t$', '$k_t$', '$\mu_t$']

titles = ['Consumption', 'Capital', 'Lagrange Multiplier']

c_paths = []

k_paths = []

for T in T_arr:

c_vec, k_vec = bisection(pp, c0, k0, T, k_ter=k_ter, verbose=False)

c_paths.append(c_vec)

k_paths.append(k_vec)

μ_vec = pp.u_prime(c_vec)

paths = [c_vec, k_vec, μ_vec]

for i in range(3):

axs[i].plot(paths[i])

axs[i].set(xlabel='t', ylabel=ylabels[i], title=titles[i])

# Plot steady state value of capital

if k_ss is not None:

axs[1].axhline(k_ss, c='k', ls='--', lw=1)

axs[1].axvline(T+1, c='k', ls='--', lw=1)

axs[1].scatter(T+1, paths[1][-1], s=80)

return c_paths, k_paths

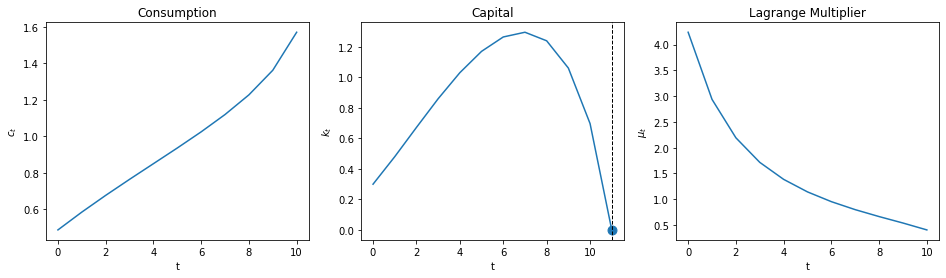

Now we can solve the model and plot the paths of consumption, capital, and Lagrange multiplier.

plot_paths(pp, 0.3, 0.3, [10]);

20.5. Setting Initial Capital to Steady State Capital¶

When \(T \rightarrow +\infty\), the optimal allocation converges to steady state values of \(C_t\) and \(K_t\).

It is instructive to set \(K_0\) equal to the \(\lim_{T \rightarrow + \infty } K_t\), which we’ll call steady state capital.

In a steady state \(K_{t+1} = K_t=\bar{K}\) for all very large \(t\).

Evalauating the feasibility constraint (20.4) at \(\bar K\) gives

Substituting \(K_t = \bar K\) and \(C_t=\bar C\) for all \(t\) into (20.12) gives

Defining \(\beta = \frac{1}{1+\rho}\), and cancelling gives

Simplifying gives

and

For the production function (20.3) this becomes

As an example, after setting \(\alpha= .33\), \(\rho = 1/\beta-1 =1/(19/20)-1 = 20/19-19/19 = 1/19\), \(\delta = 1/50\), we get

Let’s verify this with Python and then use this steady state \(\bar K\) as our initial capital stock \(K_0\).

ρ = 1 / pp.β - 1

k_ss = pp.f_prime_inv(ρ+pp.δ)

print(f'steady state for capital is: {k_ss}')

steady state for capital is: 9.57583816331462

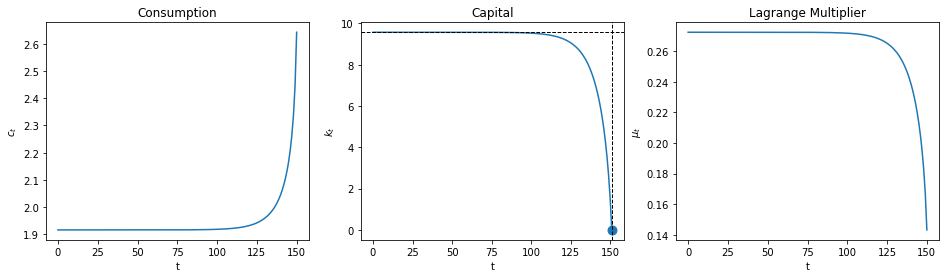

Now we plot

plot_paths(pp, 0.3, k_ss, [150], k_ss=k_ss);

Evidently, with a large value of \(T\), \(K_t\) stays near \(K_0\) until \(t\) approaches \(T\) closely.

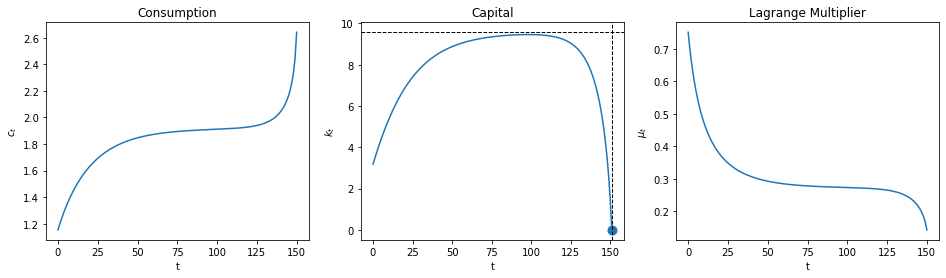

Let’s see what the planner does when we set \(K_0\) below \(\bar K\).

plot_paths(pp, 0.3, k_ss/3, [150], k_ss=k_ss);

Notice how the planner pushes capital toward the steady state, stays near there for a while, then pushes \(K_t\) toward the terminal value \(K_{T+1} =0\) when \(t\) closely approaches \(T\).

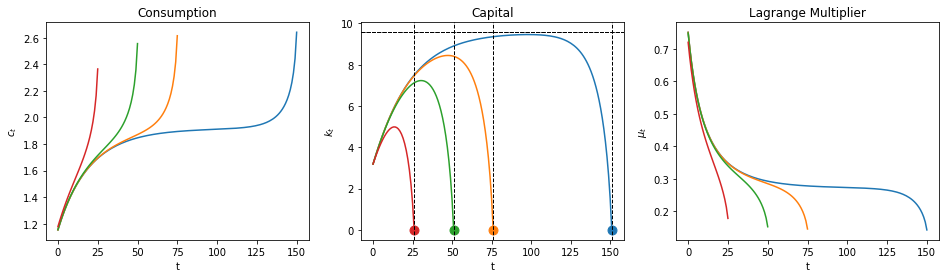

The following graphs compare optimal outcomes as we vary \(T\).

plot_paths(pp, 0.3, k_ss/3, [150, 75, 50, 25], k_ss=k_ss);

20.6. A Turnpike Property¶

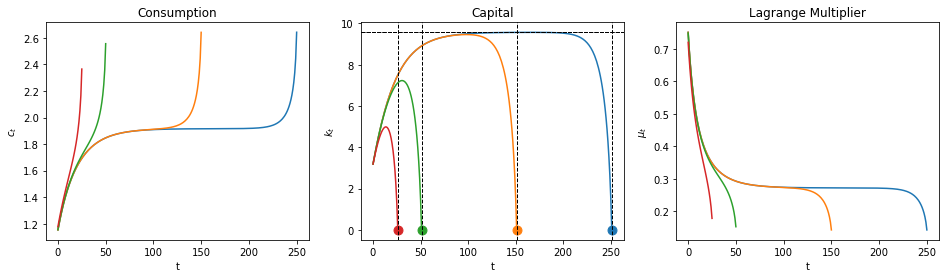

The following calculation indicates that when \(T\) is very large, the optimal capital stock stays close to its steady state value most of the time.

plot_paths(pp, 0.3, k_ss/3, [250, 150, 50, 25], k_ss=k_ss);

Different colors in the above graphs are associated with different horizons \(T\).

Notice that as the horizon increases, the planner puts \(K_t\) closer to the steady state value \(\bar K\) for longer.

This pattern reflects a turnpike property of the steady state.

A rule of thumb for the planner is

from \(K_0\), push \(K_t\) toward the steady state and stay close to the steady state until time approaches \(T\).

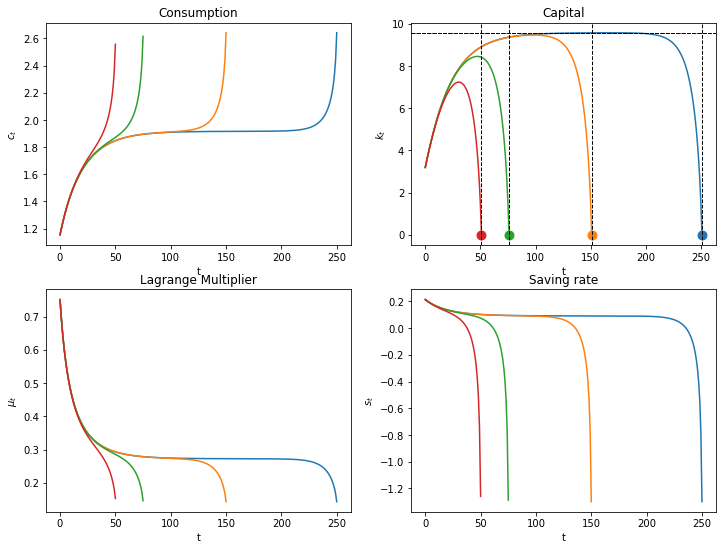

The planner accomplishes this by adjusting the saving rate \(\frac{f(K_t) - C_t}{f(K_t)}\) over time.

Let’s calculate and plot the saving rate.

@njit

def saving_rate(pp, c_path, k_path):

'Given paths of c and k, computes the path of saving rate.'

production = pp.f(k_path[:-1])

return (production - c_path) / production

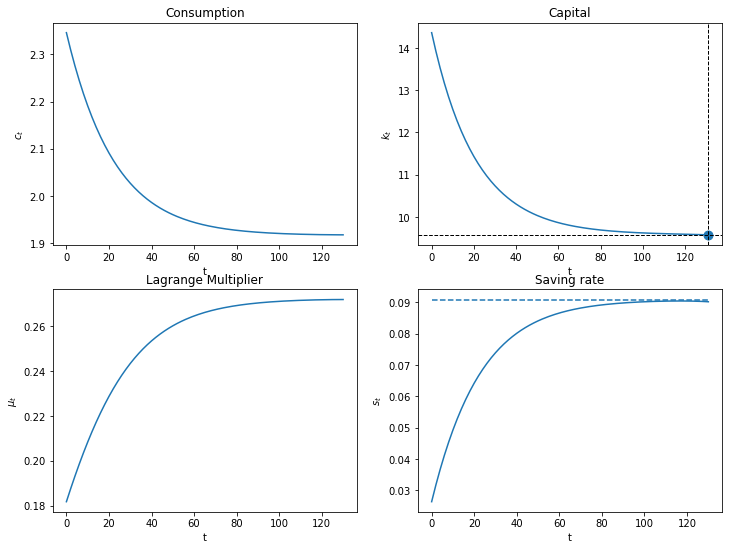

def plot_saving_rate(pp, c0, k0, T_arr, k_ter=0, k_ss=None, s_ss=None):

fix, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(12, 9))

c_paths, k_paths = plot_paths(pp, c0, k0, T_arr, k_ter=k_ter, k_ss=k_ss, axs=axs.flatten())

for i, T in enumerate(T_arr):

s_path = saving_rate(pp, c_paths[i], k_paths[i])

axs[1, 1].plot(s_path)

axs[1, 1].set(xlabel='t', ylabel='$s_t$', title='Saving rate')

if s_ss is not None:

axs[1, 1].hlines(s_ss, 0, np.max(T_arr), linestyle='--')

plot_saving_rate(pp, 0.3, k_ss/3, [250, 150, 75, 50], k_ss=k_ss)

20.7. A Limiting Economy¶

We want to set \(T = +\infty\).

The appropriate thing to do is to replace terminal condition (20.10) with

a condition that will be satisfied by a path that converges to an optimal steady state.

We can approximate the optimal path by starting from an arbitrary initial \(K_0\) and shooting towards the optimal steady state \(K\) at a large but finite \(T+1\).

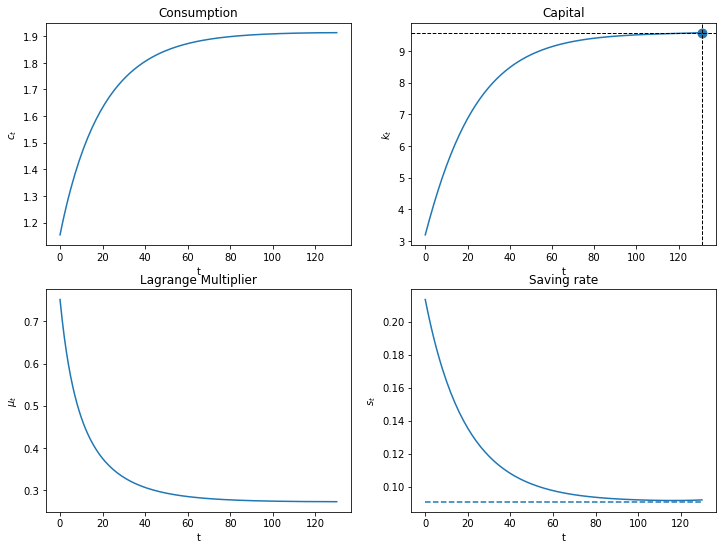

In the following code, we do this for a large \(T\) and plot consumption, capital, and the saving rate.

We know that in the steady state that the saving rate is constant and that \(\bar s= \frac{f(\bar K)-\bar C}{f(\bar K)}\).

From (20.13) the steady state saving rate equals

The steady state saving rate \(\bar S = \bar s f(\bar K)\) is the amount required to offset capital depreciation each period.

We first study optimal capital paths that start below the steady state.

# steady state of saving rate

s_ss = pp.δ * k_ss / pp.f(k_ss)

plot_saving_rate(pp, 0.3, k_ss/3, [130], k_ter=k_ss, k_ss=k_ss, s_ss=s_ss)

Since \(K_0<\bar K\), \(f'(K_0)>\rho +\delta\).

The planner chooses a positive saving rate that is higher than the steady state saving rate.

Note, \(f''(K)<0\), so as \(K\) rises, \(f'(K)\) declines.

The planner slowly lowers the saving rate until reaching a steady state in which \(f'(K)=\rho +\delta\).

20.7.1. Exercise¶

Plot the optimal consumption, capital, and saving paths when the initial capital level begins at 1.5 times the steady state level as we shoot towards the steady state at \(T=130\).

Why does the saving rate respond as it does?

20.7.2. Solution¶

plot_saving_rate(pp, 0.3, k_ss*1.5, [130], k_ter=k_ss, k_ss=k_ss, s_ss=s_ss)

20.8. Concluding Remarks¶

In Cass-Koopmans Competitive Equilibrium, we study a decentralized version of an economy with exactly the same technology and preference structure as deployed here.

In that lecture, we replace the planner of this lecture with Adam Smith’s invisible hand

In place of quantity choices made by the planner, there are market prices somewhat produced by the invisible hand.

Market prices must adjust to reconcile distinct decisions that are made independently by a representative household and a representative firm.

The relationship between a command economy like the one studied in this lecture and a market economy like that studied in Cass-Koopmans Competitive Equilibrium is a foundational topic in general equilibrium theory and welfare economics.