Quantitative Economics with Python

LLN and CLT

6. LLN and CLT¶

Contents

6.1. Overview¶

This lecture illustrates two of the most important theorems of probability and statistics: The law of large numbers (LLN) and the central limit theorem (CLT).

These beautiful theorems lie behind many of the most fundamental results in econometrics and quantitative economic modeling.

The lecture is based around simulations that show the LLN and CLT in action.

We also demonstrate how the LLN and CLT break down when the assumptions they are based on do not hold.

In addition, we examine several useful extensions of the classical theorems, such as

The delta method, for smooth functions of random variables.

The multivariate case.

Some of these extensions are presented as exercises.

We’ll need the following imports:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (11, 5) #set default figure size

import random

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import t, beta, lognorm, expon, gamma, uniform, cauchy

from scipy.stats import gaussian_kde, poisson, binom, norm, chi2

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib.collections import PolyCollection

from scipy.linalg import inv, sqrtm

6.2. Relationships¶

The CLT refines the LLN.

The LLN gives conditions under which sample moments converge to population moments as sample size increases.

The CLT provides information about the rate at which sample moments converge to population moments as sample size increases.

6.3. LLN¶

We begin with the law of large numbers, which tells us when sample averages will converge to their population means.

6.3.1. The Classical LLN¶

The classical law of large numbers concerns independent and identically distributed (IID) random variables.

Here is the strongest version of the classical LLN, known as Kolmogorov’s strong law.

Let \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) be independent and identically distributed scalar random variables, with common distribution \(F\).

When it exists, let \(\mu\) denote the common mean of this sample:

In addition, let

Kolmogorov’s strong law states that, if \(\mathbb E |X|\) is finite, then

What does this last expression mean?

Let’s think about it from a simulation perspective, imagining for a moment that our computer can generate perfect random samples (which of course it can’t).

Let’s also imagine that we can generate infinite sequences so that the statement \(\bar X_n \to \mu\) can be evaluated.

In this setting, (6.1) should be interpreted as meaning that the probability of the computer producing a sequence where \(\bar X_n \to \mu\) fails to occur is zero.

6.3.2. Proof¶

The proof of Kolmogorov’s strong law is nontrivial – see, for example, theorem 8.3.5 of [Dud02].

On the other hand, we can prove a weaker version of the LLN very easily and still get most of the intuition.

The version we prove is as follows: If \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) is IID with \(\mathbb E X_i^2 < \infty\), then, for any \(\epsilon > 0\), we have

(This version is weaker because we claim only convergence in probability rather than almost sure convergence, and assume a finite second moment)

To see that this is so, fix \(\epsilon > 0\), and let \(\sigma^2\) be the variance of each \(X_i\).

Recall the Chebyshev inequality, which tells us that

Now observe that

Here the crucial step is at the third equality, which follows from independence.

Independence means that if \(i \not= j\), then the covariance term \(\mathbb E (X_i - \mu)(X_j - \mu)\) drops out.

As a result, \(n^2 - n\) terms vanish, leading us to a final expression that goes to zero in \(n\).

Combining our last result with (6.3), we come to the estimate

The claim in (6.2) is now clear.

Of course, if the sequence \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) is correlated, then the cross-product terms \(\mathbb E (X_i - \mu)(X_j - \mu)\) are not necessarily zero.

While this doesn’t mean that the same line of argument is impossible, it does mean that if we want a similar result then the covariances should be “almost zero” for “most” of these terms.

In a long sequence, this would be true if, for example, \(\mathbb E (X_i - \mu)(X_j - \mu)\) approached zero when the difference between \(i\) and \(j\) became large.

In other words, the LLN can still work if the sequence \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) has a kind of “asymptotic independence”, in the sense that correlation falls to zero as variables become further apart in the sequence.

This idea is very important in time series analysis, and we’ll come across it again soon enough.

6.3.3. Illustration¶

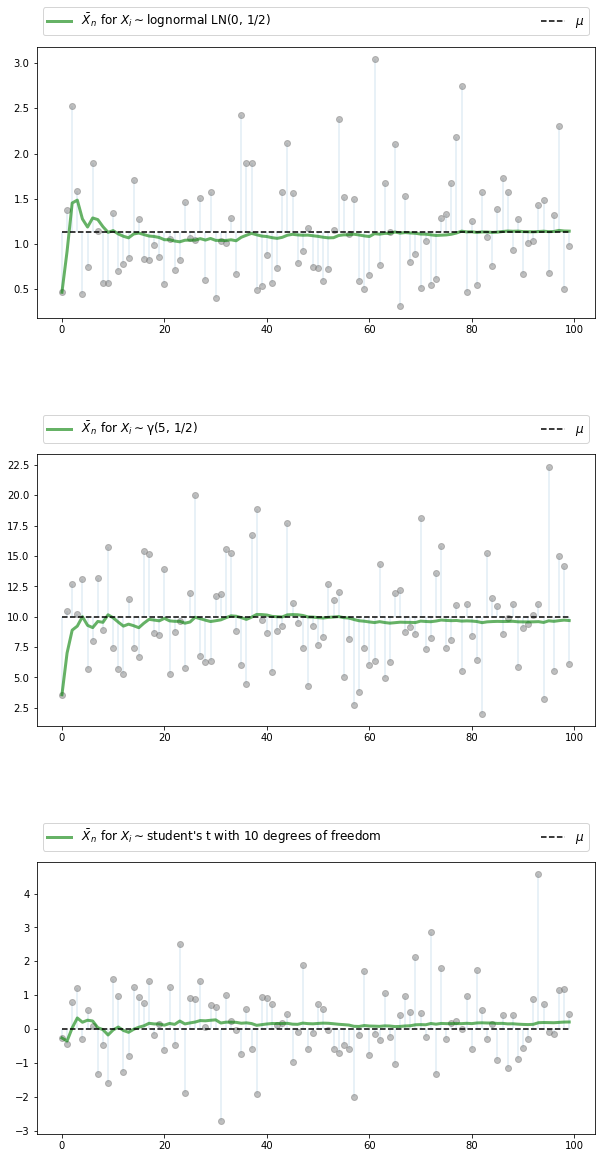

Let’s now illustrate the classical IID law of large numbers using simulation.

In particular, we aim to generate some sequences of IID random variables and plot the evolution of \(\bar X_n\) as \(n\) increases.

Below is a figure that does just this (as usual, you can click on it to expand it).

It shows IID observations from three different distributions and plots \(\bar X_n\) against \(n\) in each case.

The dots represent the underlying observations \(X_i\) for \(i = 1, \ldots, 100\).

In each of the three cases, convergence of \(\bar X_n\) to \(\mu\) occurs as predicted

n = 100

# Arbitrary collection of distributions

distributions = {"student's t with 10 degrees of freedom": t(10),

"β(2, 2)": beta(2, 2),

"lognormal LN(0, 1/2)": lognorm(0.5),

"γ(5, 1/2)": gamma(5, scale=2),

"poisson(4)": poisson(4),

"exponential with λ = 1": expon(1)}

# Create a figure and some axes

num_plots = 3

fig, axes = plt.subplots(num_plots, 1, figsize=(10, 20))

# Set some plotting parameters to improve layout

bbox = (0., 1.02, 1., .102)

legend_args = {'ncol': 2,

'bbox_to_anchor': bbox,

'loc': 3,

'mode': 'expand'}

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.5)

for ax in axes:

# Choose a randomly selected distribution

name = random.choice(list(distributions.keys()))

distribution = distributions.pop(name)

# Generate n draws from the distribution

data = distribution.rvs(n)

# Compute sample mean at each n

sample_mean = np.empty(n)

for i in range(n):

sample_mean[i] = np.mean(data[:i+1])

# Plot

ax.plot(list(range(n)), data, 'o', color='grey', alpha=0.5)

axlabel = '$\\bar X_n$ for $X_i \sim$' + name

ax.plot(list(range(n)), sample_mean, 'g-', lw=3, alpha=0.6, label=axlabel)

m = distribution.mean()

ax.plot(list(range(n)), [m] * n, 'k--', lw=1.5, label='$\mu$')

ax.vlines(list(range(n)), m, data, lw=0.2)

ax.legend(**legend_args, fontsize=12)

plt.show()

The three distributions are chosen at random from a selection stored in the dictionary distributions.

6.4. CLT¶

Next, we turn to the central limit theorem, which tells us about the distribution of the deviation between sample averages and population means.

6.4.1. Statement of the Theorem¶

The central limit theorem is one of the most remarkable results in all of mathematics.

In the classical IID setting, it tells us the following:

If the sequence \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) is IID, with common mean \(\mu\) and common variance \(\sigma^2 \in (0, \infty)\), then

Here \(\stackrel { d } {\to} N(0, \sigma^2)\) indicates convergence in distribution to a centered (i.e, zero mean) normal with standard deviation \(\sigma\).

6.4.2. Intuition¶

The striking implication of the CLT is that for any distribution with finite second moment, the simple operation of adding independent copies always leads to a Gaussian curve.

A relatively simple proof of the central limit theorem can be obtained by working with characteristic functions (see, e.g., theorem 9.5.6 of [Dud02]).

The proof is elegant but almost anticlimactic, and it provides surprisingly little intuition.

In fact, all of the proofs of the CLT that we know are similar in this respect.

Why does adding independent copies produce a bell-shaped distribution?

Part of the answer can be obtained by investigating the addition of independent Bernoulli random variables.

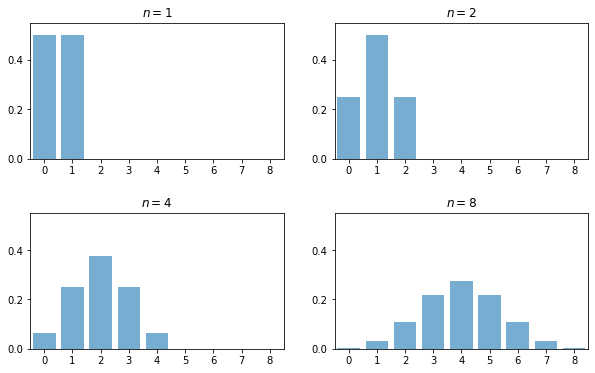

In particular, let \(X_i\) be binary, with \(\mathbb P\{X_i = 0\} = \mathbb P\{X_i = 1 \} = 0.5\), and let \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) be independent.

Think of \(X_i = 1\) as a “success”, so that \(Y_n = \sum_{i=1}^n X_i\) is the number of successes in \(n\) trials.

The next figure plots the probability mass function of \(Y_n\) for \(n = 1, 2, 4, 8\)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(10, 6))

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.4)

axes = axes.flatten()

ns = [1, 2, 4, 8]

dom = list(range(9))

for ax, n in zip(axes, ns):

b = binom(n, 0.5)

ax.bar(dom, b.pmf(dom), alpha=0.6, align='center')

ax.set(xlim=(-0.5, 8.5), ylim=(0, 0.55),

xticks=list(range(9)), yticks=(0, 0.2, 0.4),

title=f'$n = {n}$')

plt.show()

When \(n = 1\), the distribution is flat — one success or no successes have the same probability.

When \(n = 2\) we can either have 0, 1 or 2 successes.

Notice the peak in probability mass at the mid-point \(k=1\).

The reason is that there are more ways to get 1 success (“fail then succeed” or “succeed then fail”) than to get zero or two successes.

Moreover, the two trials are independent, so the outcomes “fail then succeed” and “succeed then fail” are just as likely as the outcomes “fail then fail” and “succeed then succeed”.

(If there was positive correlation, say, then “succeed then fail” would be less likely than “succeed then succeed”)

Here, already we have the essence of the CLT: addition under independence leads probability mass to pile up in the middle and thin out at the tails.

For \(n = 4\) and \(n = 8\) we again get a peak at the “middle” value (halfway between the minimum and the maximum possible value).

The intuition is the same — there are simply more ways to get these middle outcomes.

If we continue, the bell-shaped curve becomes even more pronounced.

We are witnessing the binomial approximation of the normal distribution.

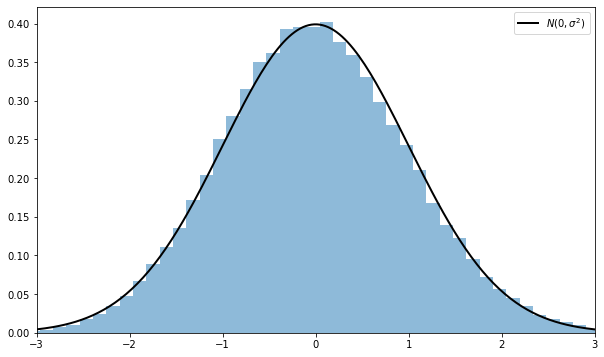

6.4.3. Simulation 1¶

Since the CLT seems almost magical, running simulations that verify its implications is one good way to build intuition.

To this end, we now perform the following simulation

Choose an arbitrary distribution \(F\) for the underlying observations \(X_i\).

Generate independent draws of \(Y_n := \sqrt{n} ( \bar X_n - \mu )\).

Use these draws to compute some measure of their distribution — such as a histogram.

Compare the latter to \(N(0, \sigma^2)\).

Here’s some code that does exactly this for the exponential distribution \(F(x) = 1 - e^{- \lambda x}\).

(Please experiment with other choices of \(F\), but remember that, to conform with the conditions of the CLT, the distribution must have a finite second moment.)

# Set parameters

n = 250 # Choice of n

k = 100000 # Number of draws of Y_n

distribution = expon(2) # Exponential distribution, λ = 1/2

μ, s = distribution.mean(), distribution.std()

# Draw underlying RVs. Each row contains a draw of X_1,..,X_n

data = distribution.rvs((k, n))

# Compute mean of each row, producing k draws of \bar X_n

sample_means = data.mean(axis=1)

# Generate observations of Y_n

Y = np.sqrt(n) * (sample_means - μ)

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

xmin, xmax = -3 * s, 3 * s

ax.set_xlim(xmin, xmax)

ax.hist(Y, bins=60, alpha=0.5, density=True)

xgrid = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, 200)

ax.plot(xgrid, norm.pdf(xgrid, scale=s), 'k-', lw=2, label='$N(0, \sigma^2)$')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

Notice the absence of for loops — every operation is vectorized, meaning that the major calculations are all shifted to highly optimized C code.

The fit to the normal density is already tight and can be further improved by increasing n.

You can also experiment with other specifications of \(F\).

6.4.4. Simulation 2¶

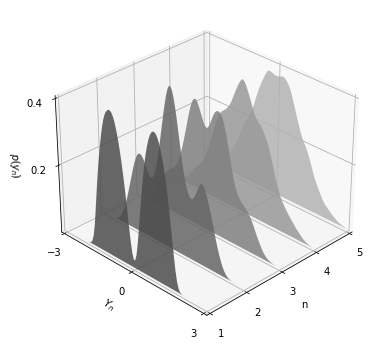

Our next simulation is somewhat like the first, except that we aim to track the distribution of \(Y_n := \sqrt{n} ( \bar X_n - \mu )\) as \(n\) increases.

In the simulation, we’ll be working with random variables having \(\mu = 0\).

Thus, when \(n=1\), we have \(Y_1 = X_1\), so the first distribution is just the distribution of the underlying random variable.

For \(n=2\), the distribution of \(Y_2\) is that of \((X_1 + X_2) / \sqrt{2}\), and so on.

What we expect is that, regardless of the distribution of the underlying random variable, the distribution of \(Y_n\) will smooth out into a bell-shaped curve.

The next figure shows this process for \(X_i \sim f\), where \(f\) was specified as the convex combination of three different beta densities.

(Taking a convex combination is an easy way to produce an irregular shape for \(f\).)

In the figure, the closest density is that of \(Y_1\), while the furthest is that of \(Y_5\)

beta_dist = beta(2, 2)

def gen_x_draws(k):

"""

Returns a flat array containing k independent draws from the

distribution of X, the underlying random variable. This distribution

is itself a convex combination of three beta distributions.

"""

bdraws = beta_dist.rvs((3, k))

# Transform rows, so each represents a different distribution

bdraws[0, :] -= 0.5

bdraws[1, :] += 0.6

bdraws[2, :] -= 1.1

# Set X[i] = bdraws[j, i], where j is a random draw from {0, 1, 2}

js = np.random.randint(0, 2, size=k)

X = bdraws[js, np.arange(k)]

# Rescale, so that the random variable is zero mean

m, sigma = X.mean(), X.std()

return (X - m) / sigma

nmax = 5

reps = 100000

ns = list(range(1, nmax + 1))

# Form a matrix Z such that each column is reps independent draws of X

Z = np.empty((reps, nmax))

for i in range(nmax):

Z[:, i] = gen_x_draws(reps)

# Take cumulative sum across columns

S = Z.cumsum(axis=1)

# Multiply j-th column by sqrt j

Y = (1 / np.sqrt(ns)) * S

# Plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (10, 6))

ax = fig.gca(projection='3d')

a, b = -3, 3

gs = 100

xs = np.linspace(a, b, gs)

# Build verts

greys = np.linspace(0.3, 0.7, nmax)

verts = []

for n in ns:

density = gaussian_kde(Y[:, n-1])

ys = density(xs)

verts.append(list(zip(xs, ys)))

poly = PolyCollection(verts, facecolors=[str(g) for g in greys])

poly.set_alpha(0.85)

ax.add_collection3d(poly, zs=ns, zdir='x')

ax.set(xlim3d=(1, nmax), xticks=(ns), ylabel='$Y_n$', zlabel='$p(y_n)$',

xlabel=("n"), yticks=((-3, 0, 3)), ylim3d=(a, b),

zlim3d=(0, 0.4), zticks=((0.2, 0.4)))

ax.invert_xaxis()

# Rotates the plot 30 deg on z axis and 45 deg on x axis

ax.view_init(30, 45)

plt.show()

As expected, the distribution smooths out into a bell curve as \(n\) increases.

We leave you to investigate its contents if you wish to know more.

If you run the file from the ordinary IPython shell, the figure should pop up in a window that you can rotate with your mouse, giving different views on the density sequence.

6.4.5. The Multivariate Case¶

The law of large numbers and central limit theorem work just as nicely in multidimensional settings.

To state the results, let’s recall some elementary facts about random vectors.

A random vector \(\mathbf X\) is just a sequence of \(k\) random variables \((X_1, \ldots, X_k)\).

Each realization of \(\mathbf X\) is an element of \(\mathbb R^k\).

A collection of random vectors \(\mathbf X_1, \ldots, \mathbf X_n\) is called independent if, given any \(n\) vectors \(\mathbf x_1, \ldots, \mathbf x_n\) in \(\mathbb R^k\), we have

(The vector inequality \(\mathbf X \leq \mathbf x\) means that \(X_j \leq x_j\) for \(j = 1,\ldots,k\))

Let \(\mu_j := \mathbb E [X_j]\) for all \(j =1,\ldots,k\).

The expectation \(\mathbb E [\mathbf X]\) of \(\mathbf X\) is defined to be the vector of expectations:

The variance-covariance matrix of random vector \(\mathbf X\) is defined as

Expanding this out, we get

The \(j,k\)-th term is the scalar covariance between \(X_j\) and \(X_k\).

With this notation, we can proceed to the multivariate LLN and CLT.

Let \(\mathbf X_1, \ldots, \mathbf X_n\) be a sequence of independent and identically distributed random vectors, each one taking values in \(\mathbb R^k\).

Let \(\boldsymbol \mu\) be the vector \(\mathbb E [\mathbf X_i]\), and let \(\Sigma\) be the variance-covariance matrix of \(\mathbf X_i\).

Interpreting vector addition and scalar multiplication in the usual way (i.e., pointwise), let

In this setting, the LLN tells us that

Here \(\bar{\mathbf X}_n \to \boldsymbol \mu\) means that \(\| \bar{\mathbf X}_n - \boldsymbol \mu \| \to 0\), where \(\| \cdot \|\) is the standard Euclidean norm.

The CLT tells us that, provided \(\Sigma\) is finite,

6.5. Exercises¶

6.5.1. Exercise 1¶

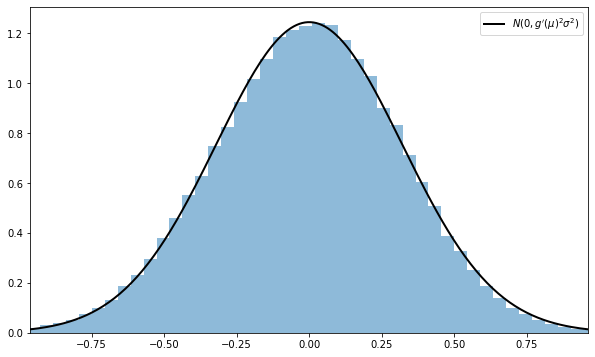

One very useful consequence of the central limit theorem is as follows.

Assume the conditions of the CLT as stated above.

If \(g \colon \mathbb R \to \mathbb R\) is differentiable at \(\mu\) and \(g'(\mu) \not= 0\), then

This theorem is used frequently in statistics to obtain the asymptotic distribution of estimators — many of which can be expressed as functions of sample means.

(These kinds of results are often said to use the “delta method”.)

The proof is based on a Taylor expansion of \(g\) around the point \(\mu\).

Taking the result as given, let the distribution \(F\) of each \(X_i\) be uniform on \([0, \pi / 2]\) and let \(g(x) = \sin(x)\).

Derive the asymptotic distribution of \(\sqrt{n} \{ g(\bar X_n) - g(\mu) \}\) and illustrate convergence in the same spirit as the program discussed above.

What happens when you replace \([0, \pi / 2]\) with \([0, \pi]\)?

What is the source of the problem?

6.5.2. Exercise 2¶

Here’s a result that’s often used in developing statistical tests, and is connected to the multivariate central limit theorem.

If you study econometric theory, you will see this result used again and again.

Assume the setting of the multivariate CLT discussed above, so that

\(\mathbf X_1, \ldots, \mathbf X_n\) is a sequence of IID random vectors, each taking values in \(\mathbb R^k\).

\(\boldsymbol \mu := \mathbb E [\mathbf X_i]\), and \(\Sigma\) is the variance-covariance matrix of \(\mathbf X_i\).

The convergence

is valid.

In a statistical setting, one often wants the right-hand side to be standard normal so that confidence intervals are easily computed.

This normalization can be achieved on the basis of three observations.

First, if \(\mathbf X\) is a random vector in \(\mathbb R^k\) and \(\mathbf A\) is constant and \(k \times k\), then

Second, by the continuous mapping theorem, if \(\mathbf Z_n \stackrel{d}{\to} \mathbf Z\) in \(\mathbb R^k\) and \(\mathbf A\) is constant and \(k \times k\), then

Third, if \(\mathbf S\) is a \(k \times k\) symmetric positive definite matrix, then there exists a symmetric positive definite matrix \(\mathbf Q\), called the inverse square root of \(\mathbf S\), such that

Here \(\mathbf I\) is the \(k \times k\) identity matrix.

Putting these things together, your first exercise is to show that if \(\mathbf Q\) is the inverse square root of \(\mathbf \Sigma\), then

Applying the continuous mapping theorem one more time tells us that

Given the distribution of \(\mathbf Z\), we conclude that

where \(\chi^2(k)\) is the chi-squared distribution with \(k\) degrees of freedom.

(Recall that \(k\) is the dimension of \(\mathbf X_i\), the underlying random vectors.)

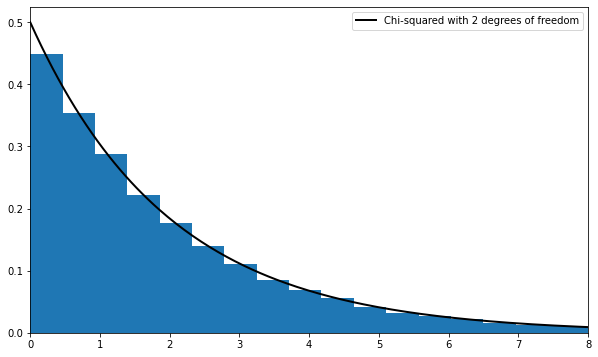

Your second exercise is to illustrate the convergence in (6.10) with a simulation.

In doing so, let

where

each \(W_i\) is an IID draw from the uniform distribution on \([-1, 1]\).

each \(U_i\) is an IID draw from the uniform distribution on \([-2, 2]\).

\(U_i\) and \(W_i\) are independent of each other.

Hints:

scipy.linalg.sqrtm(A)computes the square root ofA. You still need to invert it.You should be able to work out \(\Sigma\) from the preceding information.

6.6. Solutions¶

6.6.1. Exercise 1¶

Here is one solution

"""

Illustrates the delta method, a consequence of the central limit theorem.

"""

# Set parameters

n = 250

replications = 100000

distribution = uniform(loc=0, scale=(np.pi / 2))

μ, s = distribution.mean(), distribution.std()

g = np.sin

g_prime = np.cos

# Generate obs of sqrt{n} (g(X_n) - g(μ))

data = distribution.rvs((replications, n))

sample_means = data.mean(axis=1) # Compute mean of each row

error_obs = np.sqrt(n) * (g(sample_means) - g(μ))

# Plot

asymptotic_sd = g_prime(μ) * s

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

xmin = -3 * g_prime(μ) * s

xmax = -xmin

ax.set_xlim(xmin, xmax)

ax.hist(error_obs, bins=60, alpha=0.5, density=True)

xgrid = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, 200)

lb = "$N(0, g'(\mu)^2 \sigma^2)$"

ax.plot(xgrid, norm.pdf(xgrid, scale=asymptotic_sd), 'k-', lw=2, label=lb)

ax.legend()

plt.show()

What happens when you replace \([0, \pi / 2]\) with \([0, \pi]\)?

In this case, the mean \(\mu\) of this distribution is \(\pi/2\), and since \(g' = \cos\), we have \(g'(\mu) = 0\).

Hence the conditions of the delta theorem are not satisfied.

6.6.2. Exercise 2¶

First we want to verify the claim that

This is straightforward given the facts presented in the exercise.

Let

By the multivariate CLT and the continuous mapping theorem, we have

Since linear combinations of normal random variables are normal, the vector \(\mathbf Q \mathbf Y\) is also normal.

Its mean is clearly \(\mathbf 0\), and its variance-covariance matrix is

In conclusion, \(\mathbf Q \mathbf Y_n \stackrel{d}{\to} \mathbf Q \mathbf Y \sim N(\mathbf 0, \mathbf I)\), which is what we aimed to show.

Now we turn to the simulation exercise.

Our solution is as follows

# Set parameters

n = 250

replications = 50000

dw = uniform(loc=-1, scale=2) # Uniform(-1, 1)

du = uniform(loc=-2, scale=4) # Uniform(-2, 2)

sw, su = dw.std(), du.std()

vw, vu = sw**2, su**2

Σ = ((vw, vw), (vw, vw + vu))

Σ = np.array(Σ)

# Compute Σ^{-1/2}

Q = inv(sqrtm(Σ))

# Generate observations of the normalized sample mean

error_obs = np.empty((2, replications))

for i in range(replications):

# Generate one sequence of bivariate shocks

X = np.empty((2, n))

W = dw.rvs(n)

U = du.rvs(n)

# Construct the n observations of the random vector

X[0, :] = W

X[1, :] = W + U

# Construct the i-th observation of Y_n

error_obs[:, i] = np.sqrt(n) * X.mean(axis=1)

# Premultiply by Q and then take the squared norm

temp = Q @ error_obs

chisq_obs = np.sum(temp**2, axis=0)

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

xmax = 8

ax.set_xlim(0, xmax)

xgrid = np.linspace(0, xmax, 200)

lb = "Chi-squared with 2 degrees of freedom"

ax.plot(xgrid, chi2.pdf(xgrid, 2), 'k-', lw=2, label=lb)

ax.legend()

ax.hist(chisq_obs, bins=50, density=True)

plt.show()